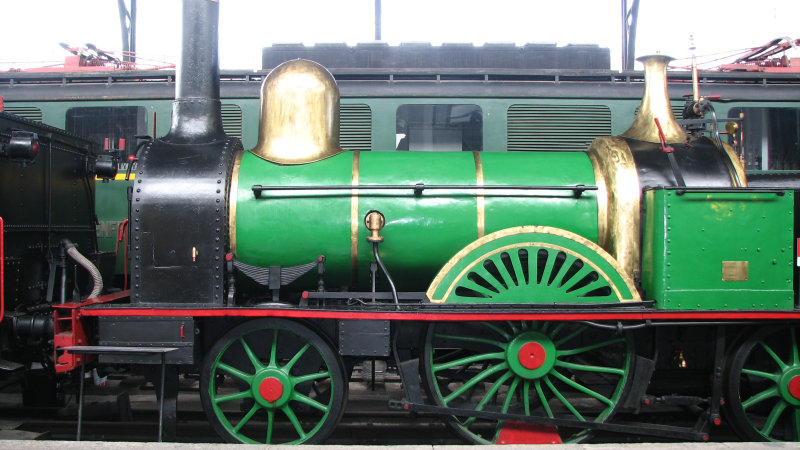

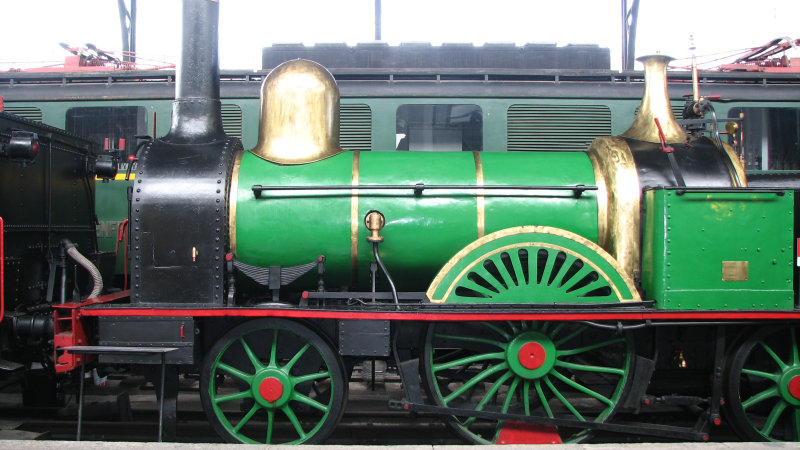

Old train engine at Madrid’s train museum

Trains have improved immensely over the last twenty odd years. Gone are the ten-hour overnight expreso trains with people selling sandwiches through the windows. Gone are the scratchy-plush seats, the long unexplained delays in nameless towns, unintelligible but important announcements on the PA system. Now most Spanish trains are punctual, clean, comfortable, well-appointed, sensibly scheduled and on-schedule.

Trains are more comfortable for long trips than buses or cars, are not subject to highway traffic returning to the city, don’t make people motion-sick and if you’ve got kids, might make a long trip easier because you can move around instead of just sitting. There are some drawbacks: they’re not always faster or less expensive than other kinds of transportation, they’re subject to schedules that may not be exactly your own, and they don’t go absolutely everywhere. But they’re a good option for people want to explore Spain, especially for a getaway weekend to a city or the beach, when you don’t need your car at destination.

For some Spanish train history and a bit of trivia, see the end of this post.

Getting information on the Renfe website, a quick guide: This is a quick instead of detailed guide because Renfe train company reorganizes frequently to highlight offers, so what is top right today may be bottom center next week. The website is huge and quite informative; it’s also partly in Spanish, so get out your dictionary or sit down with a Spanish speaker. (Language link at top right, but not all pages are translated)

What is what, what is where: Renfe divides their service into three types by distance: Larga Distancia, Media Distancia and Cercanias (Long, middle and short distance). The Cercanias are mostly commuter trains are based on twelve different urban nuclei like Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao, Malaga. The Media Distancia trains now correspond to the Autonomous Communities and generally speaking are within a single Community or at most, entering a neighboring one. Larga Distancia trains usually cross several regions.

The next division is the kind of trains. The fastest are Alta Velocidad (AVE, the high-speed bullet trains) and the Avant: AVE is usually long distance and Avant short or middle distance, but some destinations have both types with different schedules and different prices. Other fairly fast trains are the Talgo, Alvia and Alaris, followed by the shorter-run Regional Express. The overnight Tren-Hotel is quite nice, far better than the almost extinct overnight Estrella. The classic Regional trains are less expensive and much slower, but sometimes are the only option for isolated areas. FEVE trains are only in the north, an older narrow-gauge system now operated by Renfe.

Schedules: For Cercanias commuter trains look for backwards C in a red circle and select your urban nucleus. You will probably need to tell the system the exact origin and destination stations (Madrid city has several) to get what you want. For middle and long distance trains look for Horarios y Precios (Timetables and Prices). That link takes you to the core of the website, where you get your schedules, special deals, and learn about how to travel with your bike, pets, kids or golf clubs.

Finding the deals: Go to the center of home page under Promociones y Ofertas (Prices and Discounts). Take your time here – it’s one of the sections that has not been fully translated and there are some great deals: round trip, frequent travelers, elders or kids. . . one of the best deals is the “Tarifa 4 Mesa” , where you get a 60% discount buying four seats on the AVE or other long-distance trains that have four facing seats at the end of the car (two facing backwards), often with a small table in between. You have to buy all four, but with that discount even if you use only three seats it’s still a great deal, and you’ll have a little more space. There’s something similar (though not such a big discount), for taking the entire compartment on overnight trains.

Payment, what’s new: In the past paying with plastic on this site has been difficult until credit card is “activated” by Renfe, but I think they now accept PayPal. That said, a Renfe person told me confidentially that sometimes the best deals don’t appear for electronic purchase – she had just given me a 50% discount on two different trips. So sometimes it’s worth getting the information on the website and going in person to get the tickets, especially if you’re doing something special.

See the trains: Want to know more about the trains, including photos inside and out, or maybe discover where your seat is located? Look for Nuestros Trenes (Our Trains). You’ll need to know the train model, usually linked to the itinerary. Click on model name and follow the prompts.

Trenes touristicos (Tourist trains): This is one of the sections that moves around a lot, if it is not visible on home page look again once on the page for medium and long distance schedules. The special trains can be days trips to cultural sights with themed entertainment on the train (Medieval train to Siguenza, Cervantes train), wine themed in Extremadura or Galicia or even a multi-day “cruise” through fabulous scenery on a period train like the Al-Andalus, Transcantábrico or the Robla. These trains usually do not run year-round but they’re a fun option. (Madrid’s Strawberry Train is not operated by Renfe).

All in all, maybe for your next trip you should take the train!

Website: Renfe: www.renfe.com For all the schedules and information explained above

The train in Spain, some history: Plans for Spanish trains were discussed as early as 1830, but the first train was in 1848 – a 28 kilometer line from Barcelona to Mataro. The second line was 49 kilometers between Madrid and Aranjuez (1851), probably thanks to Queen Isabel II’s fondness for the Aranjuez Palace.

Spain’s early years of train service were euphoric but chaotic. No overall plan was created for a rail network, and a multitude of private companies built rail systems to serve specific areas, often with little or no connection with other areas or with other companies. That was the situation until around 1926, when the dictator Primo de Rivera tried to create a logical rail network, connecting existing rail lines and making plans for the future. It was an ambitious, necessary project, but the Civil War (1936-1939) brought reorganization to a grinding halt.

The war destroyed rails, bridges, stations and the trains themselves. Most of the private train companies were bankrupt and unable to make the necessary repairs, so in 1941 the Spanish state nationalized all train lines to create RENFE, Red Nacional de Ferrocarriles Españoles (Spanish National Network of Train Lines). As a state-run monopoly, Renfe managed all aspects of Spanish rail service until December 31, 2004.

On that date, following EU mandates on free commerce, Renfe ended its 63-year lifespan. On January 1, 2005, two new companies came existance: Adif for infrastructure and Renfe-Operadora for service (ticketing and all services to clients, freight). For now Renfe-Operadora has the inside track (pardon the pun) on managing the services, with regional companies in Cataluña, the Basque country and a few other places. Theoretically in the future this could change, though the logistical hurdles would be huge.

Fun train trivia:

Track gauge (width): Iberian train tracks have a different width from the rest of Europe: the traditional rail width in Spain and Portugal is 1,668mm (aprox 66 in.), and most of Europe is 1,435mm (aprox 57 in.). Spanish lore says that the Iberian rail width was purposely made different from international rail width so the French couldn’t invade by train – the Napoleonic occupation still a recent memory in the mid 1800’s. A more plausible technical explanation for the wider track width is that Spanish geography was more challenging in distances and hills, so a wider track width would permit more powerful train engines. In any case, now all new rail construction like the bullet train is done to international rail gauge, and a recent proposal suggests changing all of Spain’s rail system to international width. In the north the company FEVE runs a narrow – gauge (via estrecha) network with a 1000mm (about 39 in.) track width.

Distances: Spain has over 12,000 kilometers (7,460 miles) of classic track in service, and more than 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles) of high speed “bullet” tracks. In addition to converting the classic track to international width, Spain hopes to become a world leader for high-speed train service – they’re already in the top three, ahead of other Euro-Land countries like Germany and France.

AVE train speed: maximum speed is 310 kilometers / hour (193 miles) maximum speed, though they usually travel at closer to 200 kilometers (124 miles).

Red cap, red baton and whistle: Spain’s trains are entirely computerized and most road-track crossroads have been eliminated. But there’s one remaining bit of human control in many stations, including some near though not in Madrid city: the stationmaster confirms train departure manually, by dashing (or sauntering) out of the station, red cap and baton in hand. He or she goes to the platform where train is scheduled to depart, does a visual check , dons the red cap, raises the red baton and blows the whistle. This is fun to watch for – and an inside source (his wife is stationmaster) says that indeed, without the red hat the train engineers do not pay attention.